Practice Test 1 - AP English Language and Composition

Section I

TIME: 1 HOUR

DIRECTIONS: Questions 1–11. Carefully read the following passage and answer the accompanying questions.

The passage below is excerpted from a memoir published in the mid-20th century.

Passage 1

You can live a lifetime and, at the end of it, know more about other people than you know about yourself. You learn to watch other people, but you never watch yourself because you strive against loneliness. If you read a book, or shuffle a deck of cards, or care for a dog, you are avoiding yourself. The abhorrence of loneliness is as natural as wanting to live at all. If (5)it were otherwise, men would never have bothered to make an alphabet, nor to have fashioned words out of what were only animal sounds, nor to have crossed continents—each man to see what the other looked like.

Being alone in an aeroplane even for so short a time as a night and a day, irrevocably alone, with nothing to observe but your instruments and your own hands in semi-darkness, (10)nothing to contemplate but the size of your small courage, nothing to wonder about but the beliefs, the faces, and the hopes rooted in your mind—such an experience can be as startling as the first awareness of a stranger walking by your side at night. You are a stranger. It is dark already and I am over the south of Ireland. There are the lights of Cork and the lights are wet; they are drenched with Irish rain, and I am above them and dry. I am above them (15)and the plane roars in a sobbing world, but it imparts no sadness to me. I feel the security of solitude, the exhilaration of escape. So long as I can see the lights and imagine the people walking underneath them, I feel selfishly triumphant, as if I have eluded care and left even the small sorrow of rain in other hands.

It is a little over an hour now since I left Abingdon, England. Wales and the Irish Sea are (20)behind me like so much time used up. On a long flight distance and time are the same. But there had been a moment when Time stopped—and Distance too. It was the moment I lifted the blue-and-silver Gull from the aerodrome, the moment the photographers aimed their cameras, the moment I felt the craft refuse its burden and strain toward the earth in sullen rebellion, only to listen at last to the persuasion of stick and elevators, the dogmatic (25)argument of blueprints that said she had to fly because the figures proved it. So she had flown, and once airborne, once she had yielded to the sophistry of a draughtsman’s board, she had said, “There, I have lifted the weight. Now, where are we bound?”—and the question had frightened me.

We are bound for a place thirty-six hundred miles from here—two thousand miles of it (30)unbroken ocean. Most of the way it will be night. We are flying west with the night. So there behind me is Cork; and ahead of me is Berehaven Lighthouse. It is the last light, standing on the last land. I watch it, counting the frequency of its flashes—so many to the minute. Then I pass it and fly out to sea.

The fear is gone now—not overcome nor reasoned away. It is gone because something (35)else has taken its place; the confidence and the trust, the inherent belief in the security of land underfoot—now this faith is transferred to my plane, because land has vanished and there is no other tangible thing to fix faith upon. Flight is but momentary escape from the eternal custody of earth. . . .

(1942)

1. The rhetorical purpose of using the second-person pronoun “you” in the opening lines of the passage is meant primarily to

(A) explain how difficult it is for people to understand themselves.

(B) show that the speaker refuses to admit she’s thinking of herself.

(C) create the effect that the writer is addressing “you,” the reader.

(D) indicate that the narrator is giving advice to an undefined audience.

(E) comment on the human experience, particularly the narrator’s own.

2. In lines 3–4, the speaker makes a hypothetical statement about loneliness primarily to

(A) make a point about the dynamics of interpersonal relationships.

(B) introduce the idea that pain is part of the human condition.

(C) account for the need to be active in various endeavors.

(D) generalize about why we are interested in stories of other people.

(E) provide examples of everyday activities.

3. In line 9 and after, the writer constructs three sentences that begin with “nothing to (followed by a verb) but. . . .” The effect of this repetition is best described by which of the following?

(A) It simulates the monotony often experienced on long, uneventful airplane flights.

(B) It heightens readers’ anticipation to learn what the narrator will substitute for the rejected verb.

(C) It adds surprise to the narrative, an element meant to entertain readers.

(D) It dramatizes a crucial motif of the passage—the narrator’s sense of discovery.

(E) It adds to the adventure of crossing three thousand miles of water in a small airplane.

4. The rhetorical purpose of switching from second-person to first-person narration in line 12 is mainly to

(A) explain the meaning of “You are a stranger” (line 12).

(B) indicate that until then the narrator hasn’t been thinking only about herself.

(C) give an example of the “abhorrence of loneliness” (line 4).

(D) emphasize that the narrator acknowledges how alone she now really is.

(E) prove that the narrator is an accomplished pilot.

5. The rhetorical function of the phrase “sobbing world” (line 15) is primarily to

(A) describe the rain outside the airplane.

(B) suggest the pulsating sounds of the airplane engine.

(C) explain the sadness of lonely people.

(D) reveal the narrator’s affection for the Irish people far below.

(E) indicate that flying serves as a release from everyday cares.

6. In context, lines 8–18 (“Being alone . . . in other hands) could be used to support which of the following claims about the writer’s tone?

(A) Her tone while describing her solitude in the sky is buoyant.

(B) Her tone when looking down at cities below is sentimental.

(C) She adopts an awed tone when referring to the darkness outside.

(D) She adopts a nonchalant tone when contemplating her courage.

(E) She adopts a reverent tone when referring to people on the ground below.

7. The sentence in line 20 (“On a long . . . same”) has all of the following rhetorical functions EXCEPT

(A) to present information about the way pilots tend to think.

(B) to introduce the anecdote that follows in lines 20–28.

(C) to illustrate how pilots on long solo flights sometimes may become disoriented.

(D) to help contrast the tedium of long-distance flying with the thrill of taking off.

(E) to explain the phrase “like so much time used up” (line 20).

8. Which of the following best characterizes the writer’s decision to undertake a long solo flight?

(A) The irony of flying solo in order to escape loneliness

(B) The need to overcome fears of inadequacy

(C) A means to escape from routine

(D) An effort to assuage feelings of self-doubt about her capabilities

(E) An amorphous desire to make a name for herself

9. All of the following interpretations explain the rhetorical purpose in line 21 of capitalizing “Time” and “Distance” EXCEPT

(A) to support the narrator’s previous claim that on long flights “distance and time are the same” (line 20).

(B) to indicate that suddenly becoming airborne is the equivalent of a metaphysical moment that, in effect, transforms reality.

(C) in the context, to emphasize the significance of the moment when the plane became airborne.

(D) to imply that during a solo flight Time and Distance assume the stature of a deity in the mind of a pilot.

(E) to suggest that Time and Distance become virtually palpable during the experience of flying solo.

10. In the third paragraph (lines 19–28), which of the following rhetorical strategies is most prominent?

(A) Emphasizing sensual imagery

(B) Using abstract generalizations

(C) Mixing facts and impressions

(D) Appealing to authority

(E) Employing periodic sentences

11. The primary rhetorical effect of the paragraph in lines 29–33 is to

(A) satisfy readers’ curiosity about the purpose of the flight.

(B) build admiration for the narrator by describing her ambitious flight plan.

(C) enrich the passage by contrasting the narrator’s impressions with factual material.

(D) give credence to such ideas as “the exhilaration of escape” (line 16) and feeling “selfishly triumphant” (line 17).

(E) indirectly explain with facts and figures what motivates the narrator to fly.

DIRECTIONS: Questions 12–25. Carefully read the following passage and answer the accompanying questions.

This is an excerpt from a speech made by a British nobleman who served in the government of Queen Victoria late in the 19th century.

Passage 2

It is no doubt true that we are surrounded by advisers who tell us that all study of the past is barren except insofar as it enables us to determine the laws by which the evolution of human societies is governed. How far such an investigation has been up to the present time fruitful in results I will not inquire. That it will ever enable us to trace with accuracy the (5)course which States and nations are destined to pursue in the future, or to account in detail for their history in the past, I do not believe.

We are borne along like travelers on some unexplored stream. We may know enough of the general configuration of the globe to be sure that we are making our way toward the ocean. We may know enough by experience or theory of the laws regulating the flow of liquids, (10)to conjecture how the river will behave under the varying influences to which it may be subject. More than this we can not know. It will depend largely upon causes which, in relation to any laws which we are ever likely to discover, may properly be called accidental, whether we are destined sluggishly to drift among fever-stricken swamps, to hurry down perilous rapids, or to glide gently through fair scenes of peaceful cultivation.

(15)But leaving on one side ambitious sociological speculations, and even those more modest but hitherto more successful investigations into the causes which have in particular cases been principally operative in producing great political changes, there are still two modes in which we can derive what I may call “spectacular” enjoyment from the study of history.

There is first the pleasure which arises from the contemplation of some great historic (20)drama, or some broad and well-marked phase of social development. The story of the rise, greatness, and decay of a nation is like some vast epic which contains as subsidiary episodes the varied stories of the rise, greatness, and decay of creeds, of parties, and of statesmen. The imagination is moved by the slow unrolling of this great picture of human mutability, as it is moved by contrasted permanence of the abiding stars. The ceaseless conflict, the strange (25)echoes of long-forgotten controversies, the confusion of purpose, the successes which lay deep the seeds of future evils, the failures that ultimately divert the otherwise inevitable danger, the heroism which struggles to the last for a cause foredoomed to defeat, the wickedness which sides with right, and the wisdom which huzzas at the triumph of folly—fate, meanwhile, through all this turmoil and perplexity, working silently toward the predestined (30)end—all these form together a subject the contemplation of which we surely never weary.

But there is yet another and very different species of enjoyment to be derived from the records of the past, which require a somewhat different method of study in order that it may be fully tasted. Instead of contemplating, as it were, from a distance, the larger aspects of the human drama, we may elect to move in familiar fellowship amid the scenes and actors of (35)special periods.

We may add to the interest we derive from the contemplation of contemporary politics, a similar interest derived from a not less minute and probably more accurate knowledge of some comparatively brief passage in the political history of the past. We may extend the social circle in which we move—a circle perhaps narrowed and restricted through circumstances beyond (40)our control—by making intimate acquaintances, perhaps even close friends, among a society long departed, but which, when we have once learnt the trick of it, it rests with us to revive.

It is this kind of historical reading which is usually branded as frivolous and useless, and persons who indulge in it often delude themselves into thinking that the real motive of their investigation into bygone scenes and ancient scandals is philosophic interest in an important (45)historical episode, whereas in truth it is not the philosophy which glorifies the details, but the details that make tolerable the philosophy.

12. The speaker’s rhetorical intent in the first sentence of the passage (lines 1–3) is made evident by all of the following EXCEPT

(A) to convey a sense of authority.

(B) to make a connection with his audience by saying “we” and “us.”

(C) to assure his audience that he’s attuned to their beliefs and values.

(D) to acknowledge that they are people of some stature.

(E) to capture the audience’s attention using hyperbole.

13. In the first paragraph, the speaker makes two negative statements: “I will not inquire” and “I do not believe.” Which of the following best explains the speaker’s rhetorical goal in saying what he won’t do and doesn’t believe?

(A) To win the audience’s confidence by speaking frankly

(B) To surprise his listeners by challenging the status quo

(C) To impress the audience with his decisiveness

(D) To reveal to the audience the obstreperous side of his personality

(E) To prepare his listeners to hear some distressing news

14. In lines 4–6 of the passage, which of the following traits of character best describes the rhetorical effect the speaker is likely to leave on his audience?

(A) That he is unwilling to take risks

(B) That he recognizes his limitations

(C) That he is proud of his accomplishments

(D) That he is an honorable public servant

(E) That he is a relentless seeker of truth

15. Which of the following best describes the rhetorical effect of lines 4–6?

(A) It reiterates the thesis of the passage.

(B) It explains the gap between historical theory and historical fact.

(C) It provides evidence that supports the previous generalization.

(D) It casts doubt on the validity of some common assumptions.

(E) It confirms the speaker’s authority to speak on the subject of the passage.

16. Considering the rhetorical imagery in the second paragraph (lines 7–14), which of the following is the best interpretation of the speaker’s position on the nature of governmental policies and planning?

(A) Anyone responsible for carrying out governmental plans should be ready to change them at any time.

(B) Good governmental policies will survive in spite of various pressures to change them.

(C) There is no way to assure the success of even the most carefully wrought plans and policies.

(D) The amount of uncertainty about the future negates the necessity for planning ahead.

(E) It’s in the nature of things that expectations for the future, however meritorious, will invariably be thwarted by countervailing forces.

17. The primary rhetorical purpose of the speaker’s extended analogy in lines 7–14 is to

(A) offer a fresh perspective on a commonly accepted belief.

(B) win the audience’s favor with a lively and amusing parable.

(C) show that serious academic controversies have a light side.

(D) demonstrate that some academic theories need not be taken literally.

(E) ridicule a widely accepted historical principle.

18. The speaker’s primary rhetorical intent in the third paragraph (lines 15–18) is to

(A) heighten the audience’s anticipation to hear what he will say about political change.

(B) present an exemplary argument against “sociological speculations.”

(C) induce his listeners to think more deeply about the causes of “great” political upheavals.

(D) dismiss customary ways of studying history in favor of a sensational new way.

(E) persuade the audience that learning history is not only worthwhile but also fun.

19. Which of the following best describes the exigence of the fourth paragraph (lines 19–30)?

(A) To describe the appeal of history over the ages

(B) To define the benefits of knowing about the past

(C) To stress the unpredictability of human events

(D) To highlight the vast sweep of history

(E) To pinpoint reasons why history needs to be studied

20. In context, lines 19–30 could be used to support which of the following statements about the speaker’s tone?

(A) His tone when discussing the impermanence of nations is ponderous.

(B) His tone when discussing humankind’s enduring conflicts is melancholy.

(C) He acquires an enthusiastic tone when discussing the variety of human experience.

(D) He adopts a bitter tone when dealing with the evil that men do.

(E) He uses a jubilant tone when speaking about the permanence of the stars.

21. The speaker’s dominant rhetorical technique in lines 19–30 is to

(A) overwhelm the audience with fleeting references to an abundance of historical events.

(B) romanticize history as a series of captivating, often inexplicable stories.

(C) exaggerate the significance of ordinary events.

(D) suggest that the sweep of history is too complex to be fully understood by one individual.

(E) imply that the audience is fortunate to be alive at the present time.

22. The main rhetorical function of the fifth paragraph (lines 31–35) is best described as

(A) an acknowledgment that some periods of history are more significant than others.

(B) an apology for having thus far ignored a number of “special periods” of history.

(C) an attempt to assuage the misgivings of some audience members.

(D) an effort to refocus the audience’s attention.

(E) a gesture of good will to non-historians in the audience.

23. While encouraging his listeners to become informed about the past (lines 39–40), the speaker embeds a parenthetical remark (“a circle . . . beyond our control”) in order to suggest that

(A) the passage of time inevitably makes data increasingly hard to retrieve.

(B) historical archives are a good source of information.

(C) much of the past can be reconstructed by examining contemporary conditions.

(D) an absence of informants caused by time, distance, or death should not be a deterrent.

(E) limiting the topic increases the chances of a comprehensive understanding of a historical period.

24. The rhetorical intent of the last sentence in the passage (lines 42–46) is mainly to

(A) impress the audience with highly charged diction such as “frivolous” and “useless.”

(B) praise the audience for its interest in the philosophy of history.

(C) point out a misconception related to the study of history.

(D) arouse the listeners’ curiosity by making reference to “ancient scandals.”

(E) leave behind a thoughtful definition of “truth” by using a paradoxical counterclaim.

25. The speaker’s shift in pronoun usage—from “I” (first person singular) in lines 1–6, to “we” (first person plural) in lines 7–41, and finally to “their” (third person) in lines 42–46)—may best be described as

(A) a device for increasing the effectiveness of his argument.

(B) a rhetorical trick designed to hold his listeners’ attention.

(C) a plan to be persuasive by keeping the audience off balance.

(D) a method for defusing potential objections to his message.

(E) a rhetorical technique meant to project an image of all-inclusiveness.

DIRECTIONS: Questions 26–33. Carefully read the following passage and answer the accompanying questions.

The passage below, adapted from an essay written in the mid-twentieth century, offers a glimpse of science through the ages.

Passage 3

(1) When you consider the whole historical evolution of science, it might be divided three ways: antiquity; classical science, starting with the Renaissance; and modern science, which started at the turn of the twentieth century. (2) In the West, for example, for more than two-thousand years, scientists subscribed to a classification system devised by the (5)Greek physician, Hippocrates. (3) His theory was that one’s innate psych-physical constitution was determined by the relative predominance within one’s body of one of the four “humors”—blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile. (4) This humoral pathology persisted into the nineteenth century. (5) What best qualifies the science of antiquity, however, is the naïve faith in the perfection of our senses and reasoning.

(10)(6) What man saw was the ultimate reality. (7) Everybody, being by necessity the center of their universe, knew there was no doubt that ours is a flat earth and man is the center. (8) There is an “up” and “down,” an absolute space, as expressed in Euclidean geometry. (9) Human reasoning was thought to lead to more reliable results than crude trial and experiment, as reflected by the dictum of Aristotle that a big stone falls faster than a small one. (10) (15)What is remarkable about this statement is not that it is wrong, but that it never occurred to Aristotle to try it. (11) He probably would have regarded such a proposal as an insult.

(12) Around two millennia later the Renaissance arrived. (13) It was a great awakening. (14) The Western mind experienced something new. (15) It was the time when Galileo, a boisterous young man, lived in Italy. (16) One day he climbed a leaning tower while carrying (20)a big stone as well as a smaller one. (17) He dropped both of them off the top, but first he had asked friends to stand at the bottom and observe which stone landed first. (18) They arrived at the same instant.

(20) This same man, doubting the perfection of his senses, later built a telescope to improve the range of his eyes, and thus discovered the rings of Saturn and the satellites of (25)Jupiter. (21) This was a dramatic discovery. (21) Galileo was but one of the first swallows of an approaching spring. (22) Somewhat earlier, Copernicus had already concluded that it was not absolutely necessary to suppose that the sun rotates around the earth; it could be the other way around. (23) Johannes Kepler agreed. (24) Using simple observation, reasoning, and careful measurement, the earth was found to move around the sun, not vice-versa.

(30)(25) Somewhat later Antony van Leeuwenhoek, a greengrocer at Delft, in Holland, improved the range of his senses by building a microscope. (26) With it he discovered a new world of living creatures too small to be seen by the naked eye. (27) Thus began the science which I will call “classical,” which reached its peak with Sir Isaac Newton, who with the concept of gravitation, made a coherent system of the universe.

(35)(28) This classical science replaced divine whims by natural laws, corrected many previous errors, and extended man’s world into both the bigger and smaller dimensions, but it introduced nothing new that man could not “understand.” (29) By the word “understand” we simply mean that we can correlate the phenomenon in question with some earlier experience of ours. (30) If I tell you that it is gravitation which holds our globe in the sun, (40)you will say “I understand,” though nobody knows what gravitation is. (31) All the same, you “understand” because you know that it is gravitation which makes apples fall, and you have all seen apples fall before.

(32) For several centuries, this classical science had little influence on everyday life. (33) Soon after, the scientific community began to speak optimistically about finding the secret (45)of life. (34) It became obvious over time that the secret of life was not to be had by a little casual experimentation, and that life in today’s terms appeared to arise only through the medium of pre-existing life.

(35) Yet, if science was not to be embarrassed by some kind of mind-matter dualism, the emergence of life had, in some way to be accounted for. (36) Nevertheless, as years passed, (50)the secret remained locked in its living jelly, in spite of larger microscopes and more formidable means of dissection. (37) The mystery was heightened because it was discovered that the supposedly simple amoeba was already a complex, self-operating chemical factory.

(38) With the failure of many efforts, science was left in the half-embarrassing position of having to postulate theories of living origins which it could not demonstrate, or at the very (55)least they thought the next generation would be in a position to do so. (39) Around the end of the nineteenth century (1896), two mysterious discoveries signified the arrival of a new period, the period of modern science. (40) One was that of Wilhelm Roentgen, who discovered new rays which could penetrate through solid matter. (41) The other was the discovery of radioactivity by Antoine Henri Becquerel, a discovery which shook the solid foundation (60)of our universe, built of indestructible matter.

26. The writer wants the first sentence of the passage (reproduced below) to catch the reader’s interest and provide a succinct introduction to its topic.

When you consider the whole historical evolution of science, it might be divided three ways: antiquity; classical science, starting with the Renaissance; and modern science, which started at the turn of the twentieth century. In the West, for example

Which version of the underlined section of the passage best achieves this goal?

(A)(as it is now)

(B)Today’s scientists argue that their discipline has had three important periods in history:

(C)The history of science is composed of three periods:

(D)The history of science may well be summarized by dividing it into three periods—

(E)Science has a history comprising three distinctive periods, namely:

27. In order to provide a more effective transition between sentences 1 and 2, the writer wants to replace part or all of the underlined section of sentence 2 (reproduced below).

In the West, for example, for more than two-thousand years, scientists subscribed to a classification system devised by the Greek physician, Hippocrates.

In the context, which would be the best choice?

(A) At first,

(B) For above two-thousand years in the West,

(C) During more than two-thousand years, in antiquity

(D) For example, during antiquity, which lasted more than two-thousand years,

(E) In antiquity, a period longer than two-thousand years,

28. The writer wants to highlight the primary features of the science in antiquity, and also add to the coherence of the discussion. To do so, the writer plans to revise sentence 5 (reproduced below)

What qualifies the science of antiquity is the naïve faith in the perfection of our senses and reasoning.

Which version most effectively serves this purpose?

(A) What epitomized the science of antiquity is the naïve faith in the perfection of our senses and reasoning.

(B) What best characterized the science of antiquity, however, was the naïve faith in the perfection of our senses and reasoning.

(C) However, the best quality of the science of antiquity was the naïve faith in the perfection of man’s senses and reasoning.

(D) What best characterizes the science of antiquity, however, may have been the naïve faith in the perfection of our senses and reasoning.

(E) What best characterizes the science of antiquity, however, was a belief, however innocent, in the perfection of our senses and of our reasoning.

29. After reading the draft of the passage, the writer singled out an excerpt (reproduced below) to be revised without altering its essential meaning.

(12) Around two millennia later the Renaissance arrived. (13) It was a great awakening. (14) The Western mind experienced something new. (15) It was the time when Galileo, a boisterous young man, lived in Italy. (16) One day he climbed a leaning tower while carrying a big stone as well as a smaller one. (17) He dropped both of them off the top, but first he had asked friends to stand at the bottom and observe which stone landed first.

Which version of sentences 12–17 best achieves those objectives?

(A) After about two-thousand years, the arrival of the Renaissance seemed to awaken the Western mind. Take as an example a boisterous young man in Italy. Galileo by name, one day he decided to carry two stones—one was big and one was small—up to the very top of a leaning tower. After previously having asked friends to observe which stone landed on the pavement first, he dropped them simultaneously.

(B) Two thousand years later, during that great awakening of the Western mind now called the Renaissance, Galileo, a boisterous young Italian, climbed a leaning tower carrying two stones, one big and one small. Having asked companions to observe which stone landed first, he dropped them simultaneously.

(C) Approximately two thousand years afterward, upon the arrival of the Renaissance, a great awakening took place in Western minds. Take, for example, the case of a young boisterous Italian named Galileo. To illustrate that the Western mind had experienced a new transformation, one day Galileo climbed up a leaning tower while carrying both a big stone and a smaller stone. From the top of the tower, he dropped both of them, but first he had asked friends to stand at the bottom and report to him which stone hit the ground first.

(D) Approximately two thousand years afterward, upon the arrival of the Renaissance, a great awakening took place in Western minds. Take, for example, the case of a young, boisterous Italian named Galileo. As an example that the Western mind had experienced something new, one day he tried an experiment and climbed a leaning tower carrying a big stone and a smaller one. He dropped both of them off the top, but first he had asked friends to stand at the bottom and watch for which one landed first.

(E) Around two millennia later the Renaissance came into history. It was a great awakening. The Western mind experienced something new. It was the time when Galileo, a boisterous Young man, lived in Italy. One day he climbed to the top of a leaning tower. He carried both a big stone and a smaller one. From the top he dropped both of them at the same moment. Beforehand, however, he had asked a couple of friends to stand at the bottom and to observe which stone landed first.

30. In sentence 21 the writer claims that the sighting of the planets’ features was “dramatic.” But left unsaid is what made it so. Which of the following sentences provides the best explanation?

(A) This was a dramatic discovery as a result of no one knew that the rings and moons existed before.

(B) This was a dramatic discovery because no one had seen the features and moons earlier.

(C) This was a dramatic discovery because nobody knew they had been there before.

(D) This was a dramatic discovery since the true facts about the rings and moons were not known before.

(E) This was a dramatic discovery; the rings and moons surprised everybody.

31. Sentences 23 and 24 (reproduced below) tell us that Kepler supported Copernicus’s findings.

(23) Johannes Kepler agreed. (24) Using simple observation, reasoning, and careful measurement, the earth was found to move around the sun, not vice-versa.

Which of the following versions best establishes the writer’s position on the nature of Kepler’s contribution to the expansion of scientific knowledge?

(A) (as it is now)

(B) Kepler confirmed Copernicus’s theory. Using simple observation, reasoning, and careful measurement, the earth was found to move around the sun, not vice-versa.

(C) Kepler confirmed Copernicus’s theories that the earth moved around the sun using simple observation, reasoning, and careful measuring, not vice-versa.

(D) Kepler used simple observation, reasoning, and careful measurement to prove that the earth moved around the sun, not vice-versa.

(E) With the use of observation, reasoning, and careful measurement, the sun was found by Kepler to support Copernicus’s theory about the earth’s movement.

32. An attentive reading of the passage suggests a disconnect in thought between sentences 32 and 33 (reprinted below).

(32) For several centuries, this classical science had little influence on everyday life. (33) Soon after, the scientific community began to speak optimistically about solving the secret of life.

Which of the following sentences would best fill that gap?

(A) At that moment qualified scholars and researchers began to speak optimistically about solving the secret of life.

(B) By the beginning of the 1900s, and then during two wars and the Great Depression, you’d hardly hear a peep about it.

(C) In search of funding, researchers appealed to government and private sources.

(D) An intellectual elite, however, wanted to look deeper into Nature’s cooking pot.

(E) On philosophical and moral grounds, some religious and conservative groups began an effort to squelch research.

33. The writer wants to add a phrase at the start of sentence 37 (reproduced below), adjusting the capitalization as needed, to set up a comparison with the idea expressed in sentence 36.

The mystery had been heightened because it was discovered that the supposedly simple amoeba was already a complex, self-operating chemical factory.

Which of the following achieves this purpose?

(A) As it happened,

(B) Furthermore,

(C) What is more,

(D) Fortuitously,

(E) By contrast,

DIRECTIONS: Questions 34–40. Carefully read the following passage and answer the accompanying questions.

The passage below is a draft.

Passage 4

(1) The history of music until about 200 A.D. is shrouded in darkness because there is virtually no extant music and little was written about it by the ancients. (2) The journey that jazz has taken can be traced with reasonable accuracy. (3) That it ripened most fully in New Orleans seems beyond dispute, although there are a few misguided deviants who (5)support other theories of its origin. (4) Even before jazz, for most New Orleanians, music wasn’t a luxury as it often is elsewhere. (5) It was a necessity. (6) Throughout the nineteenth century, diverse ethnic and racial groups—French, Spanish, and African, Italian, German, and Irish—found common cause in their love of music. (7) European folk and African-Caribbean elements merged with a popular American mainstream, causing a cultural revolution (10)that spread far and wide.

(8) Just after the beginning of the new century, jazz began to emerge as part of a broad musical revolution. (9) It encompassed ragtime, blues, spirituals, marches, and the popular fare of “Tin Pan Alley.” (10) It also reflected the profound contributions of people of African heritage to this new and distinctly American music. (11) Clearly, the need for an audience (15)was obvious for it to succeed. (12) Then, of course, there was talent for the production of it—also essential, too. (13) Moreover, success was required for there to be a favorable audience to receive and support it.

(14) Before long the local urge for musical expression was powerful. (15) Anything that could be twanged, strummed, beaten, blown, or stroked was likely to be exploited for its (20)musical usefulness. (16) For a long time the washboard was a highly respected percussion instrument, and the nimble fingers of Baby Dodds and others showed sheer genius on that workaday, washday utensil. (17) What’s more, dancing had long been a mainstay of New Orleans nightlife, and jazz performers gave dancers what they wanted. (18) During earlier decades, string bands, led by violinists, had co-managed dance work. (19) They offered (25)waltzes, quadrilles, and polkas to a polite dancing public. (20) Around 1895, however, jazz pioneers Buddy Bolden and Bunk Johnson arrived on the scene. (21) They blew their cornets in the street and in funeral parades. (22) From there it was a small step to take their music into the dance halls and clubs of their uncommonly vital city.

(23) The early development of jazz in New Orleans was also connected to the community (30)life of the city, as seen in brass band funerals, music for picnics in parks or ball games, Saturday night fish fries, and Sunday camping along the shores of Lake Ponchartrain. (24) There were also red-beans-and-rice banquets on Mondays and nightly dances at neighborhoods all over town. (25) This spirit or emotional content connected the performer to the audience. (26) It offered a musical communication in which all parties could (35)participate.

(27) By the turn of the twentieth century, instrumentation borrowed from both brass marching bands and string bands was predominant. (28) It consisted of a front line of cornet, clarinet, and trombone, and with a rhythm section of guitar, bass, and drums. (29) Dance audiences, especially the younger ones, however, craved more excitement. (30) (40)Gradually, the emergence of ragtime, blues and, later, jazz began to satisfy the demand. (31) Musicians began to redefine roles, moving away from sight-reading toward playing by ear. (32) The 1890s represented the culmination of a century of music making in the city and around the country.

(33) Stories of the twenties in Chicago and elsewhere are almost too familiar to need (45)repeating here. (34) What seems pertinent is to observe that jazz gravitated toward a particular kind of environment in which its existence was not only possible but, seen in retrospect, probable. (35) On the south side of Chicago during the twenties the New Orleans music continued an unbroken development. (36) It is not by coincidence that the decade of the 1920s has come to be known as “The Jazz Age.” (37) This was the time when jazz became (50)fashionable, as part of the youthful revolution in morals and manners that come with the “return to normalcy” following World War I.

(38) Americans were now more urbanized, affluent and entertainment-oriented than ever before. (39) The music industry was quick to take advantage of the situation. (40) In 1921, 100 million phonograph records were produced in the United States (compared (55)to 25 million in 1914). (41) Two years later production remained high at 92 million, setting a trend which continued for the better part of the decade (until the impact of radio). (42) This prosperity relied heavily on the demand of records for dancers. (43) They could be used at home for practicing the latest steps, including such exotic dances as the Shimmy, the Charleston, and the more utilitarian Fox Trot, also known as “the (60)businessman’s bounce.”

34. In order to give the passage greater coherence, the writer wants to add a phrase at the beginning of sentence 2 (reproduced below) that, adjusting for the necessary capitalization, will create a meaningful link to the idea expressed in sentence 1.

The journey that jazz has taken can be traced with reasonable accuracy.

Which of the following best achieves this goal?

(A) On the contrary,

(B) In the same vein,

(C) On the other hand,

(D) Nevertheless,

(E) Meanwhile,

35. After reviewing the draft of this passage, the writer thinks that readers may find that the tone of sentence 3 (reproduced below) is too harsh.

That it ripened most fully in New Orleans seems beyond dispute, although there are a few misguided deviants who support other theories of its origin.

Which of the following versions of the underlined text best expresses the meaning and also maintains the overall tone of the passage?

(A) Long-term doubts still persist.

(B) Not everyone agrees.

(C) Opinions of some cultural historians state other views.

(D) There are schools of thought varying on the issue.

(E) Skeptics are serious about doubting the claim.

36. In sentence 7 (reproduced below) which of the following versions of the underlined text best establishes the writer’s position on an important theme in the passage?

European folk and African-Caribbean elements merged with a popular American mainstream, causing a cultural revolution that spread far and wide.

(A) (as it is now)

(B) inspiring “good time” music delivered in a rollicking, sometimes rough, manner.

(C) creating a sound that appealed to young musicians because it was fun.

(D) a sound so addictive that many musicians never again played anything else.

(E) a combination that made New Orleans a perfect venue for jazz to take seed and thrive.

37. To make the prose more coherent, the writer wants to revise sentences 11–13 (reproduced below) and at the same time maintain their essential meaning.

(11) Clearly, the need for an audience was obvious for it to succeed. (12) Then, of course, there was talent for the production of it—also essential, too. (13) Moreover, success was required for there to be a favorable audience to receive and support it.

Which of the following versions best achieves those goals?

(A) Obviously, the music’s success needs an enthusiastic, supportive audience that needs to hear that new kind of music, and a production crew that know what they’re doing.

(B) It is clear that success depended on a favorable audience needing, supporting, and wanting to hear the music produced in a talented way.

(C) Clearly, a receptive audience is needed for success. Also a talent to produce the music.

(D) Success for this brand of music clearly depended on a need for it, a talent to produce it, and an audience to receive it.

(E) Above all, an audience is needed. Also essential are talented production crews, but most of all a desire to listen and to support it in the future.

38. The writer wants sentence 14 (reproduced below) to function as a smooth transition between paragraphs.

Before long the local urge for musical expression was powerful.

Which of the following best serves the writer’s purpose?

(A) (keep it as it is)

(B) As luck would have it, fans of jazz rejoiced.

(C) Fortunately for jazz fans, all those requirements were met.

(D) Jazz fans, it seems, got their wishes.

(E) Looking back at the situation, this was a turning point in jazz history.

39. To provide additional information, the writer may want to add the following sentence to the discussion in either the fifth or the sixth paragraph (lines 36–46).

At the same time, it was widely reported that Scott Joplin was producing ragtime on his piano at the Maple Leaf Club in Sedalia, Missouri; and in Memphis, W.C. Handy was evolving his own spectacular conception of the blues.

Where would the sentence best be placed?

(A) Before sentence 32

(B) After sentence 32, but not in the next paragraph

(C) In the new paragraph after sentence 32

(D) After sentence 33

(E) After sentence 34

40. The writer wants to add information to support the main purpose of the passage. All of the following sentences would help achieve that goal EXCEPT which one?

(A) Recordings made by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band strongly influenced the spread of jazz throughout the South and beyond.

(B) Despite the impact of racial segregation at the time, many jazz groups consisted only of black musicians.

(C) While sheet music continued to be an important medium for the popularity of new music, phonograph records were far superior.

(D) Within six months of its release, over a million recordings had been sold, thus fusing the New Orleans sound with the term “jazz” in a commercial world.

(E) Chicago became a destination for many jazz musicians who left New Orleans in search of new ideas and venues with new audiences.

DIRECTIONS: Questions 41–45. Carefully read the following passage and answer the accompanying questions.

The passage below is a draft.

Passage 5

(1) Research in the field of earthquake engineering is required, especially in places with a high to moderate seismic activity like California. (2) The lessons learned not only in 1906 but also during the 1957 and 1989 San Francisco quakes have shown the devastating effects, although at longer distances than previously known, due to extensive periods (5)of shear waves. (3) Hence, earthquake engineering research must become a priority, driven mainly by the need to predict future quakes, but also to find solutions for mitigating their effects.

(4) This sort of interest in research did not exist on April 18, 1906, when a powerful earthquake centered just off the coast grabbed San Francisco by the throat at 5:12 A.M. and nearly (10)shook it to death. (5) The magnitude 7.8 quake arrived in two pulses, the second more powerful than the first. (6) “It hurled my bed against an opposite wall, and smashed the windows. (7) Glass shards covered the floor,” wrote Emma Burke, the wife of a local attorney. (8) Above all, she recalled the deafening noise. (9) It was intense. (10) It grew increasingly louder and louder. (11) There was the crash of dishes. (12) And pictures fell from the walls. (15)(13) There was the rattle of the flat tin roof, too. (14) “Actually,” she noted long afterwards, “the groaning and the straining of the building itself made such a roar that no one noise could be distinguished.”

(15) The tragedy was compounded by the great number of people and buildings which were concentrated along the path of the fault. (16) The destruction caused by the quake (20)and the ensuing fire in the Italian Quarter resulted in the complete loss of much of the city, including the Italian Quarter, which, like other parts of the city hit by the disaster, had been reduced to a knotted, tangled mass of bent steel frames, charred bricks, and ashes. (17) In North Beach, only a small part of the community remained. (18) The Italians on Telegraph Hill, occupied by large numbers of Italians had been luckier than most, (25)although they suffered losses since insurance companies were not interested in insuring remote areas of the Hill. (19) The scattered fire hydrants and water cisterns were not to be found east of Dupont Street, and the insurance companies were not willing to gamble. (20) It was reported in the Italian press that some 20,000 Italians lost their homes in the conflagration.

(30)(21) One of the priests from the church of Sts. Peter and Paul had managed to save the consecrated host, vestments, and holy vessels. And said Mass under the inflamed sky. After the fires died, the Italians quietly returned to North Beach and tried to find the confidence to rebuild Little Italy.

(22) Approximately five to six hundred Italians had definitely left SF due to this tragic (35)event, while over six thousand new immigrants arrived and helped the survivors clear the ruins. (23) Seven hundred building permits were granted to North Beach Italian residents and businessmen to expedite the construction of the Colony. (24) Several real estate firms, such as the J. Cuneo Realtors in North Beach, demonstrated their confidence in the determination of the Italians. (25) This hastened the rebuilding process.

41. Which of the following sentences, if placed before sentence 1, would both attract readers’ attention and provide an effective introduction to the ensuing paragraph?

(A) Most people who have experienced an earthquake don’t want to do it again.

(B) After one disastrous day in April 1906, a single scientific principle became self-evident:

(C) For safety and feelings of well-being, seismic hazard assessment is a necessity everywhere on earth.

(D) The earthquake risk implication for many regions in the U.S. and throughout the world is alarming.

(E) Losses from natural hazards like earthquakes are rapidly growing, and the projected trends are unsustainable.

42. The writer wants to include a word or more at the beginning of sentence 4 (reproduced below), adjusting for capitalization as needed, in order to give the passage a more personal tone.

This sort of research and concern did not exist on April 18, 1906, when a powerful earthquake centered just off the coast grabbed San Francisco by the throat at 5:12 a.m. and nearly shook it to death.

Which of the following would best achieve that purpose?

(A) Because

(B) Without any doubt,

(C) Certainly,

(D) With regret,

(E) Alas,

43. The writer portrays Emma Burke’s experience (sentences 9–14) using several short sentences (reproduced below) written as though each event had been discrete. Without changing the basic meaning, the writer now wants to revise the text to suggest that those incidents occurred as one brief but frightening cataclysm.

(9) It was intense. (10) It grew increasingly louder and louder. (11) There was the crash of dishes. (12) And pictures fell from the walls. (13) There was the rattle of the flat tin roof, too. (14) “Actually,” she noted long afterwards, “the groaning and the straining of the building itself made such a roar that no one noise could be distinguished.”

Which version of those sentences best achieves that goal?

(A) It grew louder and louder—terrifyingly so—when all at once dishes and pictures crashed to the floor, the tin roof rattled, and the building itself strained and groaned.

(B) The terrifying noise was intense when all of a sudden our dishes crashed to the floor and pictures fell off the walls as the rattling of the flat tin roof and the strain and groan of the building was frightening.

(C) The intense noises were terrifying and grew suddenly louder with the crash of dishes and pictures on the wall while the building’s tin roof rattled and the building itself strained and groaned.

(D) The increasingly loud noise grew louder and louder as dishes fell from the shelves and pictures dropped to the floor, just as the rattle of the flat tin roof, the groaning and straining of the building itself intensified the terrifying noise.

(E) Adding to the terror was the intensifying noise of crashing dishes, pictures falling, the rattling of the flat tin roof, and the building itself straining and groaning.

44. The writer wants to add more information to the third paragraph (sentences 15–29) to support the main intent of the paragraph. All of the following pieces of evidence would help to fulfill this purpose EXCEPT which one?

(A) The burning of hazardous material and its effects on health

(B) Statistics about injuries, hospital admissions, and deaths

(C) The complete shutdown of transportation systems and its consequences

(D) A map showing population density throughout the city

(E) Hair-raising stories about couriers who worked in zones without communications

45. The writer notices a gap in continuity between sentences 24 and 25 (reproduced below), and for the sake of coherence wants to provide an appropriate idea to fill it.

Several real estate firms, such as the J. Cuneo Realtors in North Beach, demonstrated their confidence in the determination of the Italians. This hastened the rebuilding process.

Which of the following choices best meets that goal?

(A) Mortgage rates for new home purchases were deliberately left low.

(B) The company held fun-filled fundraising events to publicize the plight of many Italian families.

(C) They invested $400,000 in the reconstruction of apartments, stores, flats, and business offices.

(D) Zoning laws were discussed at public meetings of the City Council.

(E) To show good will, several Italian real estate agents were hired.

Section II

Three Essay Questions

TIME: 2 HOURS AND 15 MINUTES

Write your essays on standard 8½” × 11” composition paper. At the exam you will be given a bound booklet containing 12 lined pages.

Essay Question 1

Essay Question 2

SUGGESTED TIME: 40 MINUTES

(This question counts as one-third of the total score for Section II.)

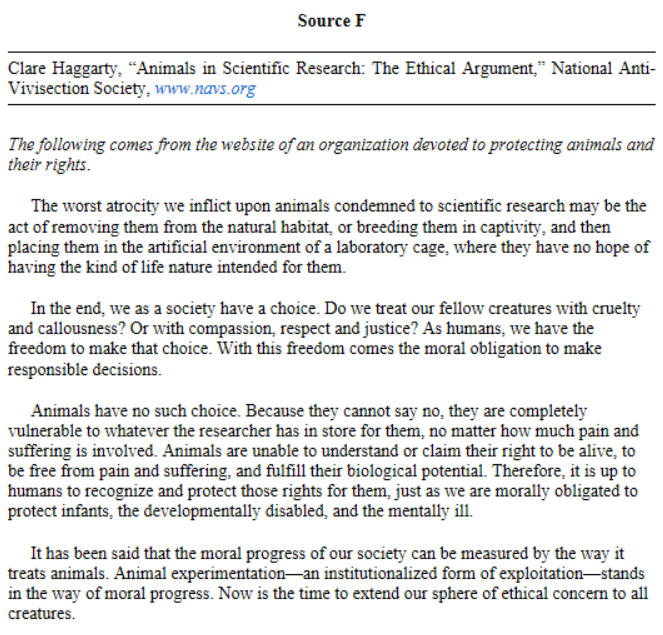

Passage A

Physics deals with “events” in space and time. To each event belongs, besides its place coordinates x, y, z, a time value t. The latter was considered measurable by a clock (ideal periodic process) of negligible spatial extent. This clock C is to be considered at rest at one point of the coordinate system, e.g., at the coordinate origin (x = y = z = 0). The time of an (5)event taking place at a point P (x,y,z) is then defined as the time shown on the clock C simultaneously with the event. Here the concept “simultaneous” was assumed as physically meaningful without special definition. This is a lack of exactness which seems harmless only since with the help of light (whose velocity is practically infinite from the point of view of daily experience) the simultaneity of spatially distant events can apparently be decided (10)immediately.

Passage B

I am convinced there is only one way to eliminate these grave ills, namely through the establishment of a socialist economy, accompanied by an educational system which would be oriented toward social goals. In such an economy, the means of production are owned by society itself and are utilized in a planned fashion. A planned economy, which adjusts production (15)to the needs of the community, would distribute work to be done among all those able to work and would guarantee a livelihood to every man, woman and child. The education of the individual, in addition to promoting his own innate abilities, would attempt to develop in him a sense of responsibility for his fellow men in place of the glorification of power and success in our present society.

(20)Nevertheless, it is necessary to remember that a planned economy is not yet socialism. A planned economy as such may be accompanied by the complete enslavement of the individual. The achievement of socialism requires the solution of some extremely difficult socio-political problems: is it possible, in view of the far-reaching centralization of political and economic power, to prevent bureaucracy from becoming all-powerful and overweening? (25)How can the rights of the individual be protected and therewith a democratic counterweight to the power of the bureaucracy be assured?

Essay Question 3

SUGGESTED TIME: 40 MINUTES

(This question counts as one-third of the total score for Section II.)

“Treat people as if they were what they ought to be and you help them to become what they are capable of being.”